Introduction

What is Algebraeon?

Algebraeon is a computer algebra system written purely in Rust. It implements algorithms for working with matrices, polynomials, algebraic numbers, factorizations, etc. The focus is on exact algebraic computations over approximate numerical solutions. A subset of the features are also available as a Python module.

Source Code and Contributing

The project is open source and is hosted on GitHub here. Contributions are welcome and should be made via GitHub.

Stability

The API is subject to large breaking changes at this time. I hope to stabilize things more in the not too distant future.

Links

Crates

Algebraeon is published to crates.io under an umbrella crate algebraeon and re-exports the sub-crates:

Algorithms

To give a flavour of what Algebraeon can do some of the algorithms it implements are listed:

- Euclids algorithm for GCD and the extended version for obtaining Bezout coefficients.

- Polynomial GCD computations using subresultant pseudo-remainder sequences.

- AKS algorithm for natural number primality testing.

- Matrix algorithms including:

- Putting a matrix into Hermite normal form. In particular putting it into echelon form.

- Putting a matrix into Smith normal form.

- Gram–Schmidt algorithm for orthogonalization and orthonormalization.

- Putting a matrix into Jordan normal.

- Finding the general solution to a linear or affine system of equations.

- Polynomial factoring algorithms including:

- Kronecker’s method for factoring polynomials over the integers (slow).

- Berlekamp-Zassenhaus algorithm for factoring polynomials over the integers.

- Berlekamp’s algorithm for factoring polynomials over finite fields.

- Cantor–Zassenhaus algorithm for factoring polynomials over finite fields.

- Trager’s algorithm for factoring polynomials over algebraic number fields.

- Expressing symmetric polynomials in terms of elementary symmetric polynomials.

- Computations with algebraic numbers:

- Real root isolation and arithmetic.

- Complex root isolation and arithmetic.

- Computations with multiplication tables for small finite groups.

- Todd-Coxeter algorithm for the enumeration of finite index cosets of a finitely generated groups.

Getting Started

As a Library

Run cargo add algebraeon in the root of your rust project to add the latest version of Algebraeon to your dependencies in your Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

algebraeon = "0.0.16"

Copy one of the example in the next section to get started.

Quickstart Examples

Factoring Integers

To factor large integers using Algebraeon

use algebraeon::nzq::Natural;

use algebraeon::rings::structure::{MetaFactoringMonoid, UniqueFactorizationMonoidSignature};

use algebraeon::sets::structure::ToStringSignature;

use std::str::FromStr;

let n = Natural::from_str("706000565581575429997696139445280900").unwrap();

let f = n.clone().factor();

println!(

"{} = {}",

n,

Natural::structure_ref().factorizations().to_string(&f)

);

/*

Output:

706000565581575429997696139445280900 = 2^2 × 5^2 × 6988699669998001 × 1010203040506070809

*/Algebraeon implements Lenstra elliptic-curve factorization for quickly finding prime factors with around 20 digits.

Factoring Polynomials

Factor the polynomials \(x^2 - 5x + 6\) and \(x^{15} - 1\).

use algebraeon::rings::{polynomial::*, structure::*};

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

let x = &Polynomial::<Integer>::var().into_ergonomic();

let f = (x.pow(2) - 5*x + 6).into_verbose();

println!("f(λ) = {}", f.factor());

/*

Output:

f(λ) = 1 * ((-2)+λ) * ((-3)+λ)

*/

let f = (x.pow(15) - 1).into_verbose();

println!("f(λ) = {}", f.factor());

/*

Output:

f(λ) = 1 * ((-1)+λ) * (1+λ+λ^2) * (1+λ+λ^2+λ^3+λ^4) * (1+(-1)λ+λ^3+(-1)λ^4+λ^5+(-1)λ^7+λ^8)

*/so

\[x^2 - 5x + 6 = (x-2)(x-3)\]

\[x^{15}-1 = (x-1)(x^2+x+1)(x^4+x^3+x^2+x+1)(x^8-x^7+x^5-x^4+x^3-x+1)\]

Linear Systems of Equations

Find the general solution to the linear system

\[a \begin{pmatrix}3 \\ 4 \\ 1\end{pmatrix} + b \begin{pmatrix}2 \\ 1 \\ 2\end{pmatrix} + c \begin{pmatrix}1 \\ 3 \\ -1\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}5 \\ 5 \\ 3\end{pmatrix}\]

for integers \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\).

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::RingToFinitelyFreeModuleSignature;

use algebraeon::rings::matrix::Matrix;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::MetaType;

let m = Matrix::<Integer>::from_rows(vec![vec![3, 4, 1], vec![2, 1, 2], vec![1, 3, -1]]);

let y = vec![5.into(), 5.into(), 3.into()];

for x in Integer::structure()

.free_module(3)

.affine_subsets()

.affine_basis(&m.row_solution_set(&y))

{

println!("{:?}", x);

}

/*

Output:

[Integer(0), Integer(2), Integer(1)]

[Integer(1), Integer(1), Integer(0)]

*/so two solutions are given by \((a, b, c) = (0, 2, 1)\) and \((a, b, c) = (1, 1, 0)\) and every solution is a linear combination of these two solutions; The general solution is given by all \((a, b, c)\) such that

\[\begin{pmatrix}a \\ b \\ c\end{pmatrix} = s\begin{pmatrix}0 \\ 2 \\ 1\end{pmatrix} + t\begin{pmatrix}1 \\ 1 \\ 0\end{pmatrix}\]

where \(s\) and \(t\) are integers such that \(s + t = 1\).

Complex Root Isolation

Find all complex roots of the polynomial \[f(x) = x^5 + x^2 - x + 1\]

use algebraeon::rings::parsing::parse_integer_polynomial;

let f = parse_integer_polynomial("x^5 + x^2 - x + 1", "x").unwrap();

// Find the complex roots of f(x)

for root in f.all_complex_roots() {

println!("root {} of degree {}", root, root.degree());

}

/*

Output:

root ≈-1.328 of degree 3

root ≈0.662-0.559i of degree 3

root ≈0.662+0.559i of degree 3

root -i of degree 2

root i of degree 2

*/

Despite the output, the roots found are not numerical approximations. Rather, they are stored internally as exact algebraic numbers by using isolating boxes in the complex plane.

Factoring Multivariable Polynomials

Factor the following multivariable polynomial with integer coefficients

\[f(x, y) = 6x^4 - 6x^3y^2 + 6xy - 6x - 6y^3 + 6y^2\]

use algebraeon::{nzq::Integer, rings::{polynomial::*, structure::*}};

let x = &MultiPolynomial::<Integer>::var(Variable::new("x")).into_ergonomic();

let y = &MultiPolynomial::<Integer>::var(Variable::new("y")).into_ergonomic();

let f = (6 * (x.pow(4) - x.pow(3) * y.pow(2) + x * y - x - y.pow(3) + y.pow(2))).into_verbose();

println!("f(x, y) = {}", f.factor());

/*

Output:

f(x, y) = 1 * ((3)1) * ((2)1) * (x+(-1)y^2) * (x^3+y+(-1)1)

*/so the factorization of \(f(x, y)\) is

\[f(x, y) = 2 \times 3 \times (x^3 + y - 1) \times (y^2 - x)\]

P-adic Root Finding

Find the \(2\)-adic square roots of \(17\).

use algebraeon::nzq::{Natural, Integer};

use algebraeon::rings::{polynomial::*, structure::*};

let x = Polynomial::<Integer>::var().into_ergonomic();

let f = (x.pow(2) - 17).into_verbose();

for mut root in f.all_padic_roots(&Natural::from(2u32)) {

println!("{}", root.truncate(&20.into()).string_repr()); // Show 20 2-adic digits

}

/*

Output:

...00110010011011101001

...11001101100100010111

*/Truncating to the last 16 bits it can be verified that, modulo \(2^{16}\), the square of these values is \(17\).

let a = 0b0010011011101001u16;

assert_eq!(a.wrapping_mul(a), 17u16);

let b = 0b1101100100010111u16;

assert_eq!(b.wrapping_mul(b), 17u16);Enumerating a Finitely Generated Group

Let \(G\) be the finitely generated group generated by \(3\) generators \(a\), \(b\), \(c\) subject to the relations \(a^2 = b^2 = c^2 = (ab)^3 = (bc)^5 = (ac)^2 = e\).

\[G = \langle a, b, c : a^2 = b^2 = c^2 = (ab)^3 = (bc)^5 = (ac)^2 = e \rangle\]

Using Algebraeon, \(G\) is found to be a finite group of order \(120\):

use algebraeon::groups::free_group::todd_coxeter::*;

let mut g = FinitelyGeneratedGroupPresentation::new();

// Add the 3 generators

let a = g.add_generator();

let b = g.add_generator();

let c = g.add_generator();

// Add the relations

g.add_relation(a.pow(2));

g.add_relation(b.pow(2));

g.add_relation(c.pow(2));

g.add_relation((&a * &b).pow(3));

g.add_relation((&b * &c).pow(5));

g.add_relation((&a * &c).pow(2));

// Count elements

let (n, _) = g.enumerate_elements();

assert_eq!(n, 120);Jordan Normal Form of a Matrix

use algebraeon::nzq::{Rational};

use algebraeon::rings::{matrix::*, isolated_algebraic::*};

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

// Construct a matrix

let a = Matrix::<Rational>::from_rows(vec![

vec![5, 4, 2, 1],

vec![0, 1, -1, -1],

vec![-1, -1, 3, 0],

vec![1, 1, -1, 2],

]);

// Put it into Jordan Normal Form

let j = MatrixStructure::new(ComplexAlgebraic::structure()).jordan_normal_form(&a);

j.pprint();

/*

Output:

/ 2 0 0 0 \

| 0 1 0 0 |

| 0 0 4 1 |

\ 0 0 0 4 /

*/Computing Discriminants

Algebraeon can find an expression for the discriminant of a polynomial in terms of the polynomials coefficients.

use algebraeon::rings::polynomial::*;

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

let a_var = Variable::new("a");

let b_var = Variable::new("b");

let c_var = Variable::new("c");

let d_var = Variable::new("d");

let e_var = Variable::new("e");

let a = MultiPolynomial::<Integer>::var(a_var);

let b = MultiPolynomial::<Integer>::var(b_var);

let c = MultiPolynomial::<Integer>::var(c_var);

let d = MultiPolynomial::<Integer>::var(d_var);

let e = MultiPolynomial::<Integer>::var(e_var);

let p =

Polynomial::<MultiPolynomial<Integer>>::from_coeffs(vec![c.clone(), b.clone(), a.clone()]);

println!("p(λ) = {}", p);

println!("disc(p) = {}", p.discriminant().unwrap());

println!();

let p = Polynomial::<MultiPolynomial<Integer>>::from_coeffs(vec![

d.clone(),

c.clone(),

b.clone(),

a.clone(),

]);

println!("p(λ) = {}", p);

println!("disc(p) = {}", p.discriminant().unwrap());

println!();

let p = Polynomial::<MultiPolynomial<Integer>>::from_coeffs(vec![

e.clone(),

d.clone(),

c.clone(),

b.clone(),

a.clone(),

]);

println!("p(λ) = {}", p);

println!("disc(p) = {}", p.discriminant().unwrap());

/*

Output:

p(λ) = (c)+(b)λ+(a)λ^2

disc(p) = (-4)ac+b^2

p(λ) = (d)+(c)λ+(b)λ^2+(a)λ^3

disc(p) = (-27)a^2d^2+(18)abcd+(-4)ac^3+(-4)b^3d+b^2c^2

*/so

\[\mathop{\text{disc}}(ax^2 + bx + c) = b^2 - 4ac\]

\[\mathop{\text{disc}}(ax^3 + bx^2 + cx + d) = b^2c^2 - 4ac^3 - 4b^3d - 27a^2d^2 + 18abcd\]

The Structure System

This section describes how Algebraeon represents the mathematical idea of sets with some additional structure such as groups, rings, fields, and so on.

Structure Types

Motivation

In mathematics there are many instances of sets with some additional structure, for example:

- The set of integers with its ordered ring structure.

- The set of rational numbers with its ordered field structure.

- For each natural number \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), the finite set of integers modulo \(n\) with its ring structure.

- The set of all algebraic numbers in \(\mathbb{C}\) with its field structure.

- The set of all ideals in a ring with the operations of ideal addition, ideal intersection, and ideal multiplication. Depending on the ring, ideals may be uniquely factorable as a product of prime ideals.

The approach taken by Algebraeon to represent such sets with additional structure is well illustrated by the example of the ring of integers modulo \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). This would be done as follows:

- Define a structure type

IntegersModuloNwhose objects shall represent the ring of integers modulo \(n\) for different values of \(n\). - Implement the desired structure by implementing signature traits on the structure type. In the case of

IntegersModuloNthe required signature traits are:Signaturethe base signature trait.SetSignature<Set = Integer>so that instances ofIntegershall be used to represent elements of the set of integers modulo \(n\).EqSignatureso that pairs ofIntegers can be tested for equality modulo \(n\).FiniteSetSignatureso that a list of all integers modulo \(n\) can be produced.SemiRingSignatureso thatIntegers can be added and multiplied modulo \(n\).RingSignatureso thatIntegers can be subtracted modulo \(n\).

In practice this looks like

use algebraeon::nzq::{Integer, Natural};

use algebraeon::rings::structure::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Eq)]

struct IntegersModuloN {

n: Natural,

}

impl Signature for IntegersModuloN {}

impl SetSignature for IntegersModuloN {

type Set = Integer;

fn is_element(&self, x: &Integer) -> Result<(), String> {

if x >= &self.n {

return Err("too big".to_string());

}

Ok(())

}

}

impl EqSignature for IntegersModuloN {

fn equal(&self, a: &Integer, b: &Integer) -> bool {

a == b

}

}

impl RinglikeSpecializationSignature for IntegersModuloN {}

impl ZeroSignature for IntegersModuloN {

fn zero(&self) -> Self::Set {

Integer::ZERO

}

}

impl AdditionSignature for IntegersModuloN {

fn add(&self, a: &Self::Set, b: &Self::Set) -> Self::Set {

((a + b) % &self.n).into()

}

}

impl CancellativeAdditionSignature for IntegersModuloN {

fn try_sub(&self, a: &Self::Set, b: &Self::Set) -> Option<Self::Set> {

Some(self.sub(a, b))

}

}

impl TryNegateSignature for IntegersModuloN {

fn try_neg(&self, a: &Self::Set) -> Option<Self::Set> {

Some(self.neg(a))

}

}

impl AdditiveMonoidSignature for IntegersModuloN {}

impl AdditiveGroupSignature for IntegersModuloN {

fn neg(&self, a: &Self::Set) -> Self::Set {

(-a % &self.n).into()

}

}

impl OneSignature for IntegersModuloN {

fn one(&self) -> Self::Set {

(Integer::ONE % &self.n).into()

}

}

impl MultiplicationSignature for IntegersModuloN {

fn mul(&self, a: &Self::Set, b: &Self::Set) -> Self::Set {

((a * b) % &self.n).into()

}

}

impl CommutativeMultiplicationSignature for IntegersModuloN {}

impl LeftDistributiveMultiplicationOverAddition for IntegersModuloN {}

impl RightDistributiveMultiplicationOverAddition for IntegersModuloN {}

impl MultiplicativeMonoidSignature for IntegersModuloN {}

impl MultiplicativeAbsorptionMonoidSignature for IntegersModuloN {}

impl SemiRingSignature for IntegersModuloN {}

impl RingSignature for IntegersModuloN {}

let mod_6 = IntegersModuloN { n: 6u32.into() };

// Since we've given `mod_6` the structure of a ring, Algebraeon implements

// the repeated squaring algorithm for taking very large powers modulo `n`.

assert!(mod_6.equal(

&mod_6.nat_pow(&2.into(), &1000000000000u64.into()),

&4.into()

));Canonical Structures

Sometimes the situation is simple and we only want to define one set with structure rather than a family of sets, for example, the set of all rational numbers. Since sets with structure are represented in Algebraeon objects of structure types we will need a structure type with exactly once instance. This can be done explicitly like so

use algebraeon::{nzq::Rational, rings::structure::*, sets::structure::*};

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Eq)]

pub struct MyRational {

value: Rational,

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Eq)]

pub struct MyRationalCanonicalStructure {}

impl Signature for MyRationalCanonicalStructure {}

impl SetSignature for MyRationalCanonicalStructure {

type Set = MyRational;

fn is_element(&self, _x: &Self::Set) -> Result<(), String> {

Ok(())

}

}

impl EqSignature for MyRationalCanonicalStructure {

fn equal(&self, x: &Self::Set, y: &Self::Set) -> bool {

x == y

}

}However, Algebraeon provides a derive macro CanonicalStructure which reduces the boilerplate above to

use algebraeon::{nzq::Rational, rings::structure::*, sets::structure::*};

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Eq, CanonicalStructure)]

pub struct MyRational {

value: Rational,

}In any case, once we have the structure type MyRationalCanonicalStructure implementing Signature + SetSignature<Set = MyRational> we can go on to implement more structure traits like RingSignature and FieldSignature for MyRationalCanonicalStructure to give the set of instances of MyRational the structure of a ring or a field.

Naming Conventions

This section outlines the naming convention used for methods relating to the structure system.

These naming convention are not settled and as such may not be used consistently. Nonetheless, this is the set of naming convention we should move towards using. We are open to suggestions on how the naming conventions could be better.

By Value and By Reference

All methods should be prefixed by into_ if they consume the structure type by value, and the into_ prefix should be omitted if they take the structure type by reference. Where both an into_ and non-into_ version of a method exist, the resulting structures should behave the same.

Constructing a Structure Type

When constructing a structure type, it is often the case that not all inputs allowed by the type system are valid. Structure types should implement a constructor of the form new(..) -> Result<Self, String> which returns Ok on valid inputs and a String explaining the invalidity on invalid inputs.

Structure types may also implement a constructor new_unchecked(..) -> Self which must panic on all inputs when compiled with debug_assertions enabled and which may result in undefined behaviour if called with an invalid input with debug_assertions disabled.

A nice pattern for implementing new and new_unchecked is to provide private methods check(&self) -> Result<(), String> and a new_impl(..) -> Result<Self, String>. They should be such that calling new_impl followed by check results in no errors if and only if the inputs were valid. Then new calls new_impl followed by check while propagating any errors, and new_unchecked calls new_impl with .unwrap(), and panics if check() fails only when debug_assertions are enabled.

Obtaining a New Structure Type in General

<>_structure may be used for methods on a structure type A which produce a new structure type B whenever A and B are structures on different things. It is also acceptable for methods of this type to not have the _structure suffix.

For example, .free_module(n) exists for any ring R and returns the free module of finite rank n.

Obtaining a New Structure Type with the Same Set

<>_restructure should be used for methods on a structure type A which produce a new structure type B whenever A and B both implement SetSignature with the same Set, meaning both use the same type for Set and is_element is Ok for A if and only if it is Ok for B on every instance of Set.

For example, .abelian_group_restructure() exists for any order in an algebraic number field (a ring whose elements are represented by Vec<Integer>s of a fixed length n) and returns the underlying rank n free abelian group structure type whose elements are also represented by Vec<Integer>s of a fixed length n. The resulting structure type is the same as that returned by .free_module(n) on the ring of integers.

Constructing Inbound Morphisms

inbound_<> should be used for methods on a structure type A which produce a Morphism from B to A for some other structure type B.

For example, .inbound_principal_integer_map() exists for any ring R and returns the unique ring homomorphism from the integers to R.

Constructing Outbound Morphisms

outbound_<> should be used for methods on a structure type A which produce a Morphism from A to B for some other structure type B.

Set Structures

Let \(X\) be a set. This section outlines the traits Algebraeon provides for defining elements of \(X\) and comparing elements with respect to equality or an ordering on \(X\).

Elements and Equality

Setfor an object representing a set of elements \(X\). Set the associated typeSetto a typeXto use instances ofXto represent elements of \(X\). It’s not necessary that all instances ofXrepresent valid elements of \(X\). The methodis_element(a: X) -> Resultshould returnOkwhenarepresents a valid element of \(X\) andErrwhen it does not. All other operations with elements of \(X\) may exhibit undefined behaviour (ideally panic immediately - at least when building debug mode).Eq : Setfor a set with a binary predicate \(=\) called equality. \(=\) is required to be an equivalence relation, meaning \[a = a \quad \forall a \in X\] \[a = b \implies b = a \quad \forall a, b \in X\] \[a = b \quad \text{and} \quad b = c \implies a = c \quad \forall a, b \in X\] The methodequal(a: X, b: X) -> boolindicates whetheraandbare equal.

Orderings

The ordering structures make use of Rusts std::cmp::Ordering enum to relay information about how elements of a set compare with respect to an ordering.

PartialOrd : Set + Eqfor sets with a binary predicate \(\le\) satisfying the axioms for a partial order. \[a \le a \quad \forall a \in X\] \[a \le b \quad \text{and} \quad b \le a \implies a = b \quad \forall a, b \in X\] \[a \le b \quad \text{and} \quad b \le c \implies a \le c \quad \forall a, b \in X\] The methodpartial_ord(a: X, b: X) -> Option<Ordering>returns information about howaandbcompare wtih respect to \(=\) and \(\le\).Ord : Set + PartialOrdfor sets with a total ordering, so in addition to the axioms for a partial ordering, \(\le\) also satisfies \[a \le b \quad \text{or} \quad b \le a \quad \forall a, b \in X\] The methodord(a: X, b: X) -> Orderingreturns information about howaandbcompare wtih respect to \(=\) and \(\le\).

Group Structures

Let \(X\) be a set. This section outlines the traits Algebraeon provides for defining group-like structures on \(X\).

Composition

Composition : Setfor a set with a binary operation called composition denoted by \(\circ\). \[\circ : X \times X \to X : (a, b) \mapsto a \circ b\].compose(a: X, b: X) -> Xis used to compute \(a \circ b\).AssociativeComposition : Compositionwhen \(\circ\) is associative \[a \circ (b \circ c) = (a \circ b) \circ c \quad \forall a, b, c \in X\]CommutativeComposition : Compositionwhen \(\circ\) is commutative \[a \circ b = b \circ a \quad \forall a, b \in X\]LeftCancellativeComposition : Compositionwhen \[a \circ x = a \circ y \implies x = y \quad \forall a, x, y \in X\] In that case the solution (or lack thereof) to \(a = b \circ x\) for \(x\) given \(a\) and \(b\) is unique whenever it exists and is computed using.try_left_difference(a: X, b: X) -> Option<X>.RightCancellativeComposition : Compositionwhen \[x \circ a = y \circ a \implies x = y \quad \forall a, x, y \in X\] In that case the solution (or lack thereof) to \(a = x \circ b\) for \(x\) given \(a\) and \(b\) is unique whenever it exists and is computed using.try_right_difference(a: X, b: X) -> Option<X>.CancellativeComposition : Composition..try_difference(a: X, b: X) -> Option<X>.

Identity

Identity : Setfor a set with a special element called the identity element which we’ll denote bye.TryLeftInverse : Identity + Compositionwhen the solution to \[x \circ a = e\] for \(x\) given \(a\) is unique whenever it exists. The solution (or lack thereof) is computed using.try_left_inverse(a: X) -> Option<X>.TryRightInverse : Identity + Compositionwhen the solution to \[a \circ x = e\] for \(x\) given \(a\) is unique whenever it exists. The solution (or lack thereof) is computed using.try_right_inverse(a: X) -> Option<X>.TryInverse: Identity + Compositionwhen the solution to \[x \circ a = a \circ x = e\] for \(x\) given \(a\) is unique whenever it exists. The solution (or lack thereof) is computed using.try_inverse(a: X) -> Option<X>.Monoid : Identity + AssociativeCompositionwhen \[a \circ e = e \circ a = a \quad \forall a \in X\]Group : TryInverse + TryLeftInverse + TryRightInverse + LeftCancellativeComposition + RightCancellativeCompositionwhen every element has an inverse. Left-, right-, and two-sided-inverses all coencide in this case and are computed using.inverse(a: X) -> X.AbelianGroup := Group + CommutativeComposition + CancellativeComposition.

Ring Structures

Let \(X\) be a set. This section outlines the traits Algebraeon provides for defining group-like structures on \(X\).

Additive Structure

Zero : Setfor a set with a special element \(0 \in X\). The methodzero() -> Xreturns an instance ofXrepresenting \(0\).Addition : Setfor a set with an associative and commutative binary operation \(+\). \[+ : X \times X \to X : (a, b) \mapsto a + b\] \[a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c \quad \forall a, b, c \in X\] \[a + b = b + a \quad \forall a, b \in X\] The methodadd(a: X, b: X) -> Xcomputes \(a + b\).CancellativeAddition : Additionwhen \[a + x = a + y \implies x = y \quad \forall a, x, y \in X\] In that case the solution (or lack thereof) to \(a = b + x\) for \(x\) given \(a\) and \(b\) is unique whenever it exists and is computed using.try_sub(a: X, b: X) -> Option<X>.TryNegate : Zero + Additionwhen the solution to \[x + a = 0\] for \(x\) given \(a\) is unique whenever it exists. The solution (or lack thereof) is computed using.try_neg(a: X) -> Option<X>.AdditiveMonoid : Zero + Addition + TryNegatewhen \[a + 0 = 0 + a = a \quad \forall a \in X\]AdditiveGroup : AdditiveMonoid + CancellativeAdditionwhen every element has an additive inverse which can be computed using.neg(a: X) -> X.

Multiplicative Structure

One : Setfor a set with a special element \(1 \in X\). The methodone() -> Xreturns an instance ofXrepresenting \(1\).Multiplication : Setfor a set with an associative binary operation \(\times\). \[\times : X \times X \to X : (a, b) \mapsto a \times b\] \[a \times (b \times c) = (a \times b) \times c \quad \forall a, b, c \in X\] The methodmul(a: X, b: X) -> Xcomputes \(a \times b\).CommutativeMultiplication : Multiplicationwhen*is commutative, soa * b = b * afor allaandb.TryLeftReciprocal : One + Multiplicationwhen the solution to \[x \times a = 1\] for \(x\) given \(a\) is unique whenever it exists. The solution (or lack thereof) is computed using.try_left_reciprocal(a: X) -> Option<X>.TryRightReciprocal : One + Multiplicationwhen the solution to \[a \times x = 1\] for \(x\) given \(a\) is unique whenever it exists. The solution (or lack thereof) is computed using.try_right_reciprocal(a: X) -> Option<X>.TryReciprocal : One + Multiplicationwhen the solution to \[x \times a = a \times x = 1\] for \(x\) given \(a\) is unique whenever it exists. The solution (or lack thereof) is computed using.try_reciprocal(a: X) -> Option<X>.MultiplicativeMonoid : One + Multiplicationwhen \[a \times 1 = 1 \times a = a \quad \forall a \in X\]

Combined Additive and Multiplicative Structure

MultiplicativeAbsorptionMonoid : MultiplicativeMonoid + Zerowhen \[a \times 0 = 0 \times a = 0 \quad \forall a \in X\]LeftDistributiveMultiplicationOverAddition : Addition + Multiplicationwhen \[a \times (b + c) = (a \times b) + (a \times c) \quad \forall a, b, c \in X\]RightDistributiveMultiplicationOverAddition : Addition + Multiplicationwhen \[(a + b) \times c = (a \times c) + (b \times c) \quad \forall a, b, c \in X\]LeftCancellativeMultiplication : Multiplication + Zerowhen \[a \times x = a \times y \implies x = y \quad \forall x, y \in X \quad a \in X \setminus \{0\}\] In that case the solution (or lack thereof) to \(a = b \times x\) for \(x\) given \(a\) and non-zero \(b\) is unique whenever it exists and is computed using.try_left_divide(a: X, b: X) -> Option<X>.Noneis also returned if \(b = 0\).RightCancellativeMultiplication : Multiplication + Zerowhen \[x \times a = y \times a \implies x = y \quad \forall x, y \in X \quad a \in X \setminus \{0\}\] In that case the solution (or lack thereof) to \(a = x \times b\) for \(x\) given \(a\) and non-zero \(b\) is unique whenever it exists and is computed using.try_right_divide(a: X, b: X) -> Option<X>.Noneis also returned if \(b = 0\).CancellativeMultiplication := Multiplication + Zero..try_divide(a: X, b: X) -> Option<X>.MultiplicativeIntegralMonoid : MultiplicativeAbsorptionMonoid + TryReciprocal + TryLeftReciprocal + TryRightReciprocal + LeftCancellativeMultiplication + RightCancellativeMultiplicationwhen \[a \times b = 0 \implies a = 0 \quad \text{or} \quad b = 0 \quad \forall a, b \in X\]

Semirings and Rings

Semiring := AdditiveMonoid + TryNegate + MultiplicativeAbsorptionMonoid + CommutativeMultiplication + DistributiveMultiplicationOverAddition.IntegralSemiring := Semiring + CancellativeMultiplication + MultiplicativeIntegralMonoid.Ring := AdditiveGroup + Semiring.IntegralDomain := Ring + MultiplicativeIntegralMonoid.EuclideanDivision : Semiringwhen there exists a norm function \[N : X \to \mathbb{N}\] computed usingnorm(a: X) -> Naturalsuch that for all \(a \in X\) and all non-zero \(b \in X\) there exists \(q, r \in X\) computed usingquorem(a: X, b: X) -> (X, X)such that \[a = qb + r \quad \text{and either} \quad N(r) < N(b) \quad \text{or} \quad r = 0\]EuclideanDomain := IntegralDomain + EuclideanDivision.

Natural Numbers

Constructing naturals

There are several ways to construct naturals. Some of them are:

Natural::ZERO,Natural::ONE,Natural::TWO- from a string:

Natural::from_str() - from builtin unsigned types

Natural::from(4u32)

use std::str::FromStr;

use algebraeon::nzq::Natural;

let one = Natural::ONE;

let two = Natural::TWO;

let n = Natural::from(42usize);

let big = Natural::from_str("706000565581575429997696139445280900").unwrap();Basic operations

Natural supports the following operators:

-

+(addition) -

*(multiplication) -

%(modulo)

For exponentiation, use the method .pow(&exp) instead of ^ (which is xor).

Available functions

chooseeuler_totientfactorfactorialgcdis_primeis_squarelcmnth_root_floornth_root_ceilsqrt_ceilsqrt_floorsqrt_if_square

use algebraeon::nzq::*;

use algebraeon::rings::structure::*;

let a = Natural::from(12u32);

let b = Natural::from(5u32);

// Basic operations

let sum = &a + &b; // 17

let product = &a * &b; // 60

let power = a.pow(&b); // 248832

let modulo = &a % &b; // 2

assert_eq!(sum, Natural::from(17u32));

assert_eq!(product, Natural::from(60u32));

assert_eq!(power, Natural::from(248832u32));

assert_eq!(modulo, Natural::from(2u32));

// Factorial

assert_eq!(b.factorial(), Natural::from(120u32));

// nth_root_floor and nth_root_ceil

assert_eq!(a.nth_root_floor(&b), Natural::from(1u32));

assert_eq!(a.nth_root_ceil(&b), Natural::from(2u32));

// sqrt_floor, sqrt_ceil, sqrt_if_square

assert_eq!(a.sqrt_floor(), Natural::from(3u32));

assert_eq!(a.sqrt_ceil(), Natural::from(4u32));

let square = Natural::from(144u32); // 12²

assert_eq!(square.sqrt_if_square(), Some(a.clone()));

assert_eq!(a.sqrt_if_square(), None);

// is_square

assert!(square.is_square());

assert!(!a.is_square());

// Combinatorics

assert_eq!(choose(&a, &b), Natural::from(792u32));

// GCD and LCM

assert_eq!(gcd(a.clone(), b.clone()), Natural::from(1u32));

assert_eq!(lcm(a.clone(), b.clone()), Natural::from(60u32));

// is_prime

assert!(!a.is_irreducible()); // 12 is not prime

assert!(b.is_irreducible()); // 5 is prime

// Euler's totient function

assert_eq!(

Natural::structure_ref()

.factorizations()

.euler_totient(&a.factor()),

Natural::from(4u32)

); // φ(12) = 4

assert_eq!(

Natural::structure_ref()

.factorizations()

.euler_totient(&b.factor()),

Natural::from(4u32)

); // φ(5) = 4Factoring

Algebraeon implements Lenstra elliptic-curve factorization for quickly finding prime factors up to around 20 digits.

use algebraeon::nzq::Natural;

use algebraeon::rings::structure::{MetaFactoringMonoid, UniqueFactorizationMonoidSignature};

use algebraeon::sets::structure::ToStringSignature;

use std::str::FromStr;

let n = Natural::from_str("706000565581575429997696139445280900").unwrap();

let f = n.clone().factor();

println!(

"{} = {}",

n,

Natural::structure_ref().factorizations().to_string(&f)

);

/*

Output:

706000565581575429997696139445280900 = 2^2 × 5^2 × 6988699669998001 × 1010203040506070809

*/Integers

Constructing integers

There are several ways to construct integers. Some of them are:

Integer::ZERO,Integer::ONE,Integer::TWO- from a string:

Integer::from_str() - from builtin unsigned or signed types

Integer::from(-4i32) - from a

Natural:Integer::from(Natural::TWO)

use std::str::FromStr;

use algebraeon::nzq::{Integer, Natural};

let one = Integer::ONE;

let two = Integer::TWO;

let n = Integer::from(42usize);

let m = Integer::from(-42);

let big = Integer::from_str("706000565581575429997696139445280900").unwrap();

let from_natural = Integer::from(Natural::from(5u32));Basic operations

Integer supports the following operators:

-

+(addition) -

-(subtraction or negation) -

*(multiplication) -

%(modulo)

For exponentiation, use the methods .nat_pow(&exp) or .int_pow(&exp).

Available functions

use algebraeon::nzq::{Integer, Natural};

use algebraeon::rings::structure::*;

let a = Integer::from(-12);

let b = Integer::from(5);

// Basic operations

let sum = &a + &b; // -7

let neg = -&a; // 12

let sub = &a - &b; // -17

let product = &a * &b; // -60

let power = a.nat_pow(&Natural::from(5u32)); // -248832

let modulo = &a % &b; // 3

assert_eq!(sum, Integer::from(-7));

assert_eq!(neg, Integer::from(12));

assert_eq!(sub, Integer::from(-17));

assert_eq!(product, Integer::from(-60));

assert_eq!(power, Integer::from(-248832));

assert_eq!(modulo, Integer::from(3));

// abs

use algebraeon::nzq::traits::Abs;

let abs_a = a.abs();

assert_eq!(abs_a, Natural::from(12u32));Rational Numbers

The Rational type represents a number of the form a/b, where a is an integer and b is a non-zero integer. It is a wrapper around malachite_q::Rational.

Constructing rationals

There are several ways to construct rational numbers. Some of them are:

Rational::ZERO,Rational::ONE,Rational::TWO,Rational::ONE_HALF- from a string:

Rational::from_str() - from builtin signed/unsigned types:

Rational::from(4u32),Rational::from(-3i64) - from

IntegerorNatural:Rational::from(Integer::from(-5)) - from two integers:

Rational::from_integers(n, d)

Basic operations

Rational supports the following operators:

+(addition)-(subtraction or negation)*(multiplication)/(division)

Available functions

The following methods are available on Rational:

abs()– returns the absolute valuefloor()– returns the greatest integer less than or equal to the rationalceil()– returns the smallest integer greater than or equal to the rationalapproximate(max_denominator)– approximates the rational with another having a bounded denominatorsimplest_rational_in_closed_interval(a, b)– finds the simplest rational between two boundssimplest_rational_in_open_interval(a, b)– finds the simplest rational strictly between two boundsdecimal_string_approx()– returns a decimal string approximation of the rationalexhaustive_rationals()– returns an infinite iterator over all reduced rational numbersinto_abs_numerator_and_denominator()– returns the absolute numerator and denominator asNaturalstry_from_float_simplest(x: f64)– converts a float into the simplest rational representationis_integersqrt_if_squareis_squareheight

use std::str::FromStr;

use algebraeon::nzq::{Rational, Integer, Natural};

let zero = Rational::ZERO;

let one = Rational::ONE;

let half = Rational::ONE_HALF;

let r1 = Rational::from(5u32);

let r2 = Rational::from(-3i64);

let r3 = Rational::from(Integer::from(-7));

let r4 = Rational::from(Natural::from(10u32));

let r5 = Rational::from_str("42/7").unwrap();

let r6 = Rational::from_integers(3, 4);

let a = Rational::from_str("2/3").unwrap();

let b = Rational::from_str("1/6").unwrap();

// Basic operations

let sum = &a + &b; // 5/6

let diff = &a - &b; // 1/2

let product = &a * &b; // 1/9

let quotient = &a / &b; // 4

let negated = -&a; // -2/3

// Available functions

let r = Rational::from_str("-2/5").unwrap();

// abs

use algebraeon::nzq::traits::Abs;

assert_eq!(r.clone().abs(), Rational::from_str("2/5").unwrap());

// ceil

use algebraeon::nzq::traits::Ceil;

assert_eq!(r.clone().ceil(), Integer::from(0));

// floor

use algebraeon::nzq::traits::Floor;

assert_eq!(r.clone().floor(), Integer::from(-1));

// into_abs_numerator_and_denominator

use algebraeon::nzq::traits::Fraction;

let (n, d) = r.into_abs_numerator_and_denominator();

assert_eq!(n, Natural::from(2u32));

assert_eq!(d, Natural::from(5u32));

// approximate

let approx = Rational::from_str("355/113").unwrap()

.approximate(&Natural::from(10u32));

assert_eq!(approx, Rational::from_str("22/7").unwrap());

// simplest_rational_in_closed_interval

let a = Rational::from_str("2/5").unwrap();

let b = Rational::from_str("3/5").unwrap();

let simple = Rational::simplest_rational_in_closed_interval(&a, &b);

assert_eq!(simple, Rational::from_str("1/2").unwrap());

// simplest_rational_in_open_interval

let open_a = Rational::from_str("1/3").unwrap();

let open_b = Rational::from_str("2/3").unwrap();

let open_simple = Rational::simplest_rational_in_open_interval(&open_a, &open_b);

assert!(open_simple > open_a && open_simple < open_b);

// try_from_float_simplest

let from_float = Rational::try_from_float_simplest(0.5).unwrap();

assert_eq!(from_float, Rational::ONE_HALF);

// decimal_string_approx

let dec = simple.decimal_string_approx();

assert_eq!(dec, "0.5");

// Iteration

let mut iter = Rational::exhaustive_rationals();

assert_eq!(iter.next(), Some(Rational::ZERO));

assert_eq!(iter.next(), Some(Rational::ONE));Matrices

Creating Matrices

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::matrix::Matrix;

let a = Matrix::<Integer>::from_rows(vec![

vec![Integer::from(1), Integer::from(2), Integer::from(3)],

vec![Integer::from(0), Integer::from(-1), Integer::from(4)],

]);

assert_eq!(a.rows(), 2);

assert_eq!(a.cols(), 3);

let zero = Matrix::<Integer>::zero(2, 3);

let ident = Matrix::<Integer>::ident(3);

let diag = Matrix::<Integer>::diag(&vec![

Integer::from(1),

Integer::from(5),

Integer::from(9),

]);

assert_eq!(zero.rows(), 2);

assert_eq!(ident.cols(), 3);

assert_eq!(

diag.get_row(0),

vec![Integer::from(1), Integer::from(0), Integer::from(0)]

);Basic Arithmetic

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::matrix::Matrix;

let a = Matrix::<Integer>::from_rows(vec![

vec![Integer::from(1), Integer::from(2), Integer::from(3)],

vec![Integer::from(0), Integer::from(1), Integer::from(4)],

]);

let b = Matrix::<Integer>::from_rows(vec![

vec![Integer::from(1), Integer::from(0)],

vec![Integer::from(0), Integer::from(1)],

vec![Integer::from(2), Integer::from(3)],

]);

let sum = Matrix::add(&a, &a).unwrap();

let product = Matrix::mul(&a, &b).unwrap();

assert_eq!(

sum.get_row(0),

vec![Integer::from(2), Integer::from(4), Integer::from(6)]

);

assert_eq!(

product.get_row(0),

vec![Integer::from(7), Integer::from(11)]

);

assert_eq!(

product.get_row(1),

vec![Integer::from(8), Integer::from(13)]

);

let scaled = a.clone().mul_scalar(&Integer::from(3));

let transposed = b.clone().transpose();

assert_eq!(

scaled.get_row(1),

vec![Integer::from(0), Integer::from(3), Integer::from(12)]

);

assert_eq!(

transposed.get_row(0),

vec![Integer::from(1), Integer::from(0), Integer::from(2)]

);use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::matrix::Matrix;

let v = Matrix::<Integer>::from_rows(vec![vec![

Integer::from(1),

Integer::from(2),

Integer::from(3),

]]);

let w = Matrix::<Integer>::from_rows(vec![vec![

Integer::from(4),

Integer::from(5),

Integer::from(6),

]]);

assert_eq!(Matrix::dot(&v, &w), Integer::from(32));Determinants, Rank, and Inverses

use algebraeon::nzq::{Integer, Rational};

use algebraeon::rings::matrix::Matrix;

let integer_matrix = Matrix::<Integer>::from_rows(vec![

vec![Integer::from(1), Integer::from(2)],

vec![Integer::from(3), Integer::from(5)],

]);

assert_eq!(

integer_matrix.clone().det().unwrap(),

Integer::from(-1)

);

assert_eq!(integer_matrix.rank(), 2);

let rational_matrix = Matrix::<Rational>::from_rows(vec![

vec![Rational::from(2), Rational::from(4), Rational::from(4)],

vec![Rational::from(-6), Rational::from(6), Rational::from(12)],

vec![Rational::from(10), Rational::from(7), Rational::from(17)],

]);

let inverse = Matrix::inv(&rational_matrix).unwrap();

assert_eq!(Matrix::mul(&rational_matrix, &inverse).unwrap(), Matrix::ident(3));Free Modules

This section explains how to work with free modules, submodules and cosets of submodules.

If \(R\) is a commutative ring then the set \(R^n\) of all length \(n\) tuples of elements from \(R\) is a free \(R\)-module with standard basis \(e_1, \dots, e_n \in R^n\). \[e_1 = (1, 0, \dots, 0)\] \[e_2 = (0, 1, \dots, 0)\] \[\vdots\] \[e_n = (0, 0, \dots, 1)\]

Algebraeon supports working with free modules over the following rings \(R\):

- The integers \(\mathbb{Z}\)

- The rationals \(\mathbb{Q}\)

- Any field

- Any Euclidean domain

The examples in this section primarily illustrate how to use Algebraeon in the case \(R = \mathbb{Z}\).

Free Modules

The free module \(R^n\) is represented by objects of type FinitelyFreeModuleStructure. A free module structure can be obtained from the ring of scalars by calling .free_module(n) (the module will take the scalar ring structure by reference) or .into_free_module(n) (the module will take ownership of the scalar ring structure).

For example, to obtain \(\mathbb{Z}^3\)

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::RingToFinitelyFreeModuleSignature;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::MetaType;

let module = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3);Elements of \(\mathbb{Z}^3\) are represented by objects of type Vec<Integer> and basic operations with the elements are provided by the module structure.

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::*;

use algebraeon::rings::structure::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

let module = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3);

let a = vec![1.into(), 2.into(), 3.into()];

let b = vec![(-1).into(), 2.into(), (-2).into()];

assert!(module.equal(

&module.neg(&a),

&vec![(-1).into(), (-2).into(), (-3).into()]

));

assert!(

module.equal(&module.add(&a, &b),

&vec![0.into(), 4.into(), 1.into()]

));

assert!(

module.equal(&module.sub(&a, &b),

&vec![2.into(), 0.into(), 5.into()]

));

assert!(module.equal(

&module.scalar_mul(&a, &5.into()),

&vec![5.into(), 10.into(), 15.into()]

));The scalar ring structure can be obtained from a module by calling .ring().

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

let module = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3);

let ring = module.ring();

assert_eq!(ring, &Integer::structure());Submodules

The set of submodules of the free module \(R^n\) is represented by objects of type FinitelyFreeSubmoduleStructure. This structure can be obtained from a module by calling .submodules() (the structure will take the module structure by reference) or .into_submodules() (the structure will take ownership of the module structure).

For example, to obtain the set of all submodules of \(\mathbb{Z}^3\)

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

let submodules = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3).into_submodules();Submodules of \(R^n\) are represented by objects of type FinitelyFreeSubmodule.

Constructing Submodules

The zero submodule \({0} \subseteq R^n\) can be constructed using .zero_submodule() and the full submodule \(R^n \subseteq R^n\) can be constructed using .full_submodule().

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

let submodules = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3).into_submodules();

assert_eq!(submodules.zero_submodule().rank(), 0);

assert_eq!(submodules.full_submodule().rank(), 3);The submodule given by the span of some elements of the module can be constructed using .span(..).

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

let submodules = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3).into_submodules();

assert_eq!(

submodules

.span(vec![

&vec![1.into(), 2.into(), 2.into()],

&vec![2.into(), 1.into(), 1.into()],

&vec![3.into(), 3.into(), 3.into()]

])

.rank(),

2

);The submodule given by the kernel of some elements can be constructed using .kernel(..).

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

let submodules = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3).into_submodules();

assert!(submodules.equal(

&submodules.kernel(vec![

&vec![1.into(), 2.into()],

&vec![2.into(), 1.into()],

&vec![3.into(), 3.into()],

]),

&submodules.span(vec![&vec![1.into(), 1.into(), (-1).into()]])

));Basic Operations

Test submodules for equality using .equal(..).

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

let submodules = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3).into_submodules();

assert!(submodules.equal(

&submodules.span(vec![

&vec![2.into(), 2.into(), 0.into()],

&vec![2.into(), (-2).into(), 0.into()],

]),

&submodules.span(vec![

&vec![4.into(), 0.into(), 0.into()],

&vec![0.into(), 4.into(), 0.into()],

&vec![2.into(), 2.into(), 0.into()],

])

));

assert!(!submodules.equal(

&submodules.span(vec![

&vec![1.into(), 1.into(), 0.into()],

&vec![2.into(), 3.into(), 0.into()],

]),

&submodules.span(vec![

&vec![1.into(), 2.into(), 3.into()],

&vec![1.into(), 1.into(), 0.into()],

])

));Check whether a submodule contains an element using .contains_element(..).

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

let submodules = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3).into_submodules();

let a = submodules.span(vec![

&vec![2.into(), 2.into(), 0.into()],

&vec![2.into(), (-2).into(), 0.into()],

]);

assert!(submodules.contains_element(&a, &vec![4.into(), 4.into(), 0.into()]));

assert!(!submodules.contains_element(&a, &vec![3.into(), 4.into(), 0.into()]));

assert!(!submodules.contains_element(&a, &vec![4.into(), 4.into(), 1.into()]));Check whether a submodule is a subset of another submodule using .contains(..).

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

let submodules = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3).into_submodules();

let a = submodules.span(vec![&vec![3.into(), 3.into(), 3.into()]]);

let b = submodules.span(vec![&vec![6.into(), 6.into(), 6.into()]]);

assert!(submodules.contains(&a, &b));

assert!(!submodules.contains(&b, &a));Compute the sum of two submodules using .sum(..) and compute the intersection of two submodules using .intersection(..).

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::module::finitely_free_module::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

let submodules = Integer::structure().into_free_module(3).into_submodules();

let a = submodules.span(vec![&vec![4.into(), 4.into(), 4.into()]]);

let b = submodules.span(vec![&vec![6.into(), 6.into(), 6.into()]]);

let sum_ab = submodules.span(vec![&vec![2.into(), 2.into(), 2.into()]]);

assert!(submodules.equal(&submodules.add(a.clone(), b.clone()), &sum_ab));

let intersect_ab = submodules.span(vec![&vec![12.into(), 12.into(), 12.into()]]);

assert!(submodules.equal(&submodules.intersect(a.clone(), b.clone()), &intersect_ab));Multivariate Polynomials

Example

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::polynomial::*;

use algebraeon::rings::structure::*;

use std::collections::HashMap;

// Define symbols for the variables we wish to use

let x_var = Variable::new("x");

let y_var = Variable::new("y");

// Construct the polynomials x and y from the variables

let x = &MultiPolynomial::<Integer>::var(x_var.clone());

let y = &MultiPolynomial::<Integer>::var(y_var.clone());

// x and y can now be used just like other ring elements in Algebraeon

let f = MultiPolynomial::add(x, y).nat_pow(&3u32.into());

// f = x^3+(3)x^2y+(3)xy^2+y^3

println!("f = {}", f);

// For evaluating f the inputs are specified using the variable symbols

let v = f.evaluate(HashMap::from([(x_var, &1.into()), (y_var, &2.into())]));

// v = f(1, 2) = 27

println!("v = {}", v);Algebraic Numbers

Let \(F\) and \(K\) be fields with \(F \subseteq K\). A number \(\alpha \in K\) is said to be algebraic over \(F\) if there exists a polynomial \(p(x) \in F[x]\) such that \(f(\alpha) = 0\). If \(\alpha \in K\) is algebraic over \(F\) then the subset \(I\) of \(F[x]\) given by the set of all polynomials \(p(x) \in F[x]\) satisfying \(f(\alpha) = 0\) is an ideal of \(F[x]\). \[I := \{p(x) \in F[x] : p(\alpha) = 0\} \text{ is an ideal of } F[x]\] \(F[x]\) is a principal ideal domain and the unique monic polynomial \(m(x) \in F[x]\) which generates \(I\) is called the minimal polynomial of \(\alpha\).

Algebraon supports the following algebraic numbers:

- Real numbers \(\alpha \in \mathbb{R}\) which are algebraic over \(\mathbb{Q}\). Represented by the minimal polynomial \(m(x) \in \mathbb{Q}[x]\) of \(\alpha\) and a rational isolating interval \((a, b) \subseteq \mathbb{R}\) consisting a pair of rational numbers \(a, b \in \mathbb{Q}\) such that \(\alpha \in (a, b)\) and no other root of \(m(x)\) is contained in \((a, b)\).

- Complex numbers \(\alpha \in \mathbb{C}\) which are algebraic over \(\mathbb{Q}\). Represented by the minimal polynomial \(m(x) \in \mathbb{Q}[x]\) of \(\alpha\) and a rational isolating box in the complex plane.

- For a prime \(p \in \mathbb{N}\), \(p\)-adic numbers \(\alpha \in \mathbb{Q}_p\) which are algebraic over \(\mathbb{Q}\). Represented by the minimal polynomial \(m(x) \in \mathbb{Q}[x]\) of \(\alpha\) and a \(p\)-adic isolating ball consisting of a rational number \(c \in \mathbb{Q}\) and a valuation \(v \in \mathbb{N} \sqcup {\infty}\) such that \(\alpha - c\) has \(p\)-adic valuation at least \(v\) and no other root \(\beta\) of \(m(x)\) is such that \(\beta - c\) has valuation \(p\)-adic at least \(v\).

- If \(m(x) \in \mathbb{Q}[x]\) is irreducible then the quotient field \(K := \frac{\mathbb{Q}[x]}{m(x)}\) is a finite dimensional extension of \(\mathbb{Q}\), also known as an algebraic number field. Every element of \(K\) is algebraic over \(\mathbb{Q}\). Elements of \(K\) are represented by rational polynomials up to adding rational polynomial multiples of \(m(x)\).

Obtaining Polynomial Roots

This example finds all roots of a rational polynomial \(f(x) \in \mathbb{Q}[x]\) in various extension fields of \(\mathbb{Q}\). The key parts are

- Calling

.into_rational_extension()on a field \(K\) to obtain the field extension \(\mathbb{Q} \to K\). - Calling

.all_roots(&f)on a field extension \(\mathbb{Q} \to K\) to obtain all roots of \(f(x) \in \mathbb{Q}[x]\) belonging to \(K\).

use algebraeon::nzq::{Natural, Rational};

use algebraeon::rings::isolated_algebraic::ComplexAlgebraic;

use algebraeon::rings::isolated_algebraic::PAdicAlgebraic;

use algebraeon::rings::isolated_algebraic::RealAlgebraic;

use algebraeon::rings::{polynomial::*, structure::*};

use algebraeon::sets::structure::*;

// Find all roots of f in some fields

let f = Polynomial::<Rational>::from_str(

"(x - 3) * (x^2 - 17) * (x^2 + 1)", "x"

).unwrap();

println!("f = {}", f);

println!();

let two_adic = PAdicAlgebraic::structure(Natural::from(2u32))

.into_inbound_principal_rational_map();

let three_adic = PAdicAlgebraic::structure(Natural::from(3u32))

.into_inbound_principal_rational_map();

let complex = ComplexAlgebraic::structure()

.into_inbound_principal_rational_map();

let real = RealAlgebraic::structure()

.into_inbound_principal_rational_map();

let anf = Polynomial::from_str("x^2 + 1", "x")

.unwrap()

.algebraic_number_field()

.unwrap()

.into_inbound_principal_rational_map();

println!("Real roots of f");

for x in real.all_roots(&f) {

println!("{}", x);

}

println!();

println!("Complex roots of f");

for x in complex.all_roots(&f) {

println!("{}", x);

}

println!();

println!("2-adic roots of f");

for x in two_adic.all_roots(&f) {

println!("{}", x);

}

println!();

println!("3-adic roots of f");

for x in three_adic.all_roots(&f) {

println!("{}", x);

}

println!();

println!("Roots of f in Q[i]");

for x in anf.all_roots(&f) {

println!(

"{}",

x.apply_map_into(MultiPolynomial::constant).evaluate(

&Rational::structure()

.into_multivariable_polynomial_ring()

.var(Variable::new("i"))

)

);

}

/*

Output:

f = (51)+(-17)λ+(48)λ^2+(-16)λ^3+(-3)λ^4+λ^5

Real roots of f

3

-√17

√17

Complex roots of f

3

-i

i

-√17

√17

2-adic roots of f

...000011

...101001

...010111

3-adic roots of f

...000010

Roots of f in Q[i]

(3)1

i

(-1)i

*/p-Adic Algebraic Numbers

Isolated algebraic numbers in the \(p\)-adic fields \(\mathbb{Q}_p\).

Taking Square Roots

It is possible to take square roots of \(p\)-adic algebraic numbers by calling .square_roots.

use algebraeon::nzq::{Natural, Rational};

use algebraeon::rings::isolated_algebraic::PAdicAlgebraic;

use algebraeon::rings::{polynomial::*, structure::*};

let two_adic = PAdicAlgebraic::structure(Natural::from(2u32));

for x in two_adic

.inbound_principal_rational_map()

.all_roots(&Polynomial::<Rational>::from_str("(x - 3) * (x^2 - 17)", "x").unwrap())

{

println!("{} is_square={}", x, two_adic.is_square(&x));

if let Some((r1, r2)) = two_adic.square_roots(&x) {

println!(" sqrt = {} and {}", r1, r2);

}

}

/*

Output:

...000011 is_square=false

...101001 is_square=true

sqrt = ...101101 and ...010011

...010111 is_square=false

*/Ideals in Algebraic Rings of Integers

Constructing ideals

all_idealsgenerate all idealsall_ideals_norm_eqgenerate all ideals of norm equal to nall_nonzero_idealsgenerate all non-zero idealsall_nonzero_ideals_norm_legenerate all non-zero ideals of norm at most ngenerated_idealThe ideal generated by a list of elementsprincipal_idealThe principal ideal generated by aunit_idealzero_ideal

Available functions

- basis

euler_phifactor_idealaddSum of two idealsintersectIntersection of two idealsmulProduct of two idealsnat_powideal_normideal_other_generatorgiven an ideal I and element a find an element b such that I = (a, b)productProduct of many idealssumideal_two_generatorsreturn two elements which generate the idealsqrt_if_square

Available predicates

contains_idealDoes a contain b i.e. does a divide bcontains_elementequalis_zerois_prime_idealis_squarefreeis_square

Factoring example

use algebraeon::rings::algebraic_number_field::AlgebraicNumberFieldSignature;

use algebraeon::rings::algebraic_number_field::FullRankIntegerSubmoduleWithBasisSignature;

use algebraeon::rings::polynomial::PolynomialFromStr;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::InjectiveFunction;

use algebraeon::{

nzq::*,

rings::{polynomial::Polynomial, structure::*},

};

// Construct the ring of integers Z[i]

let anf = Polynomial::<Rational>::from_str("x^2+1", "x")

.unwrap()

.algebraic_number_field()

.unwrap();

let roi = anf.ring_of_integers();

// The ideal (27i - 9) in Z[i]

let ideal = roi.ideals().principal_ideal(

&roi.outbound_order_to_anf_inclusion()

.try_preimage(&Polynomial::from_str("27*x-9", "x").unwrap())

.unwrap(),

);

// Factor the ideal

for (prime_ideal, power) in roi.ideals().factor(&ideal).into_powers().unwrap() {

println!("power = {power} prime_ideal_factor = {:?}", prime_ideal);

}

// There's not yet a nice way to print ideals so the output is messy

// But it prints the following factorization into primes

// ideal = (1+i) * (1+2i) * (3)^2Continued Fractions

Computing Continued Fraction Coefficients

This example computes the first \(10\) continued fraction coefficients of \(\pi\), \(e\), and \(\sqrt[3]{2}\).

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::approximation::{e, pi};

use algebraeon::rings::continued_fraction::{

MetaToSimpleContinuedFractionSignature, SimpleContinuedFraction,

};

use algebraeon::rings::isolated_algebraic::RealAlgebraic;

use algebraeon::rings::structure::{MetaPositiveRealNthRootSignature, MetaRingSignature};

println!(

"e: {:?}",

e().simple_continued_fraction()

.iter()

.take(10)

.collect::<Vec<_>>()

);

println!(

"pi: {:?}",

pi().simple_continued_fraction()

.iter()

.take(10)

.collect::<Vec<_>>()

);

println!(

"cube_root(2): {:?}",

RealAlgebraic::from_int(Integer::from(2))

.cube_root()

.unwrap()

.simple_continued_fraction()

.iter()

.take(10)

.collect::<Vec<_>>()

);

/*

Output:

e: [Integer(2), Integer(1), Integer(2), Integer(1), Integer(1), Integer(4), Integer(1), Integer(1), Integer(6), Integer(1)]

pi: [Integer(3), Integer(7), Integer(15), Integer(1), Integer(292), Integer(1), Integer(1), Integer(1), Integer(2), Integer(1)]

cube_root(2): [Integer(1), Integer(3), Integer(1), Integer(5), Integer(1), Integer(1), Integer(4), Integer(1), Integer(1), Integer(8)]

*/We can also compute continued fractions for rational numbers, for example

\[-\frac{-5678}{1234} = -5 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{1}{30 + \cfrac{1}{4}}}}}\]

use algebraeon::{

nzq::{Integer, Rational},

rings::continued_fraction::{MetaToSimpleContinuedFractionSignature, SimpleContinuedFraction},

};

use std::str::FromStr;

assert_eq!(

Rational::from_str("-5678/1234")

.unwrap()

.simple_continued_fraction()

.iter()

.map(|x| x.as_ref().clone())

.collect::<Vec<_>>(),

vec![

Integer::from(-5),

Integer::from(2),

Integer::from(1),

Integer::from(1),

Integer::from(30),

Integer::from(4)

]

);Defining a Real Number by Its Continued Fraction Coefficients

Defining the real number

\[1 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \cfrac{1}{3 + \cfrac{1}{4 + \ddots}}} = 1.433127…\]

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::approximation::RealApproximatePoint;

use algebraeon::rings::continued_fraction::IrrationalSimpleContinuedFractionGenerator;

use algebraeon::rings::structure::MetaRealSubsetSignature;

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

struct MyContinuedFraction {

n: usize,

}

impl IrrationalSimpleContinuedFractionGenerator for MyContinuedFraction {

fn next(&mut self) -> Integer {

self.n += 1;

Integer::from(self.n)

}

}

let value =

RealApproximatePoint::from_continued_fraction(MyContinuedFraction { n: 0 }.into_continued_fraction());

println!("value = {}", value.as_f64());

/*

Output:

value = 1.4331274267223117

*/Defining the Golden Ratio

\[\varphi = 1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \ddots}}}\]

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::approximation::RealApproximatePoint;

use algebraeon::rings::continued_fraction::PeriodicSimpleContinuedFraction;

use algebraeon::rings::structure::MetaRealSubsetSignature;

let phi = RealApproximatePoint::from_continued_fraction(

PeriodicSimpleContinuedFraction::new(vec![], vec![Integer::from(1)]).unwrap(),

);

println!("phi = {}", phi.as_f64());

/*

Output:

phi = 1.618033988749895

*/

Defining \(\sqrt{2}\)

\[\sqrt{2} = 1 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \cfrac{1}{2 + \ddots}}}\]

use algebraeon::nzq::Integer;

use algebraeon::rings::approximation::RealApproximatePoint;

use algebraeon::rings::continued_fraction::PeriodicSimpleContinuedFraction;

use algebraeon::rings::structure::MetaRealSubsetSignature;

let sqrt2 = RealApproximatePoint::from_continued_fraction(

PeriodicSimpleContinuedFraction::new(vec![Integer::from(1)], vec![Integer::from(2)])

.unwrap(),

);

println!("sqrt2 = {}", sqrt2.as_f64());

/*

Output:

sqrt2 = 1.4142135623730951

*/Rational Bounds on Real Values

Compute the following rational bounds on \(\pi + e\), where the difference between the upper and lower bound is at most \(\frac{1}{100}\).

\[\frac{163994429}{28005120} < \pi + e < \frac{492403663}{84015360}\]

use algebraeon::nzq::Rational;

use algebraeon::rings::approximation::{RealApproximatePoint, e, pi};

use algebraeon::rings::structure::MetaAdditionSignature;

use std::str::FromStr;

let p = RealApproximatePoint::add(&pi(), &e());

p.lock()

.refine_to_length(&Rational::from_str("1/100").unwrap());

println!("{:?}", p.lock().rational_interval_neighbourhood());

/*

Output:

Interval(RationalInterval { a: Rational(163994429/28005120), b: Rational(492403663/84015360) })

*/Quaternion Algebras

Quaternion algebras can be created over any field: the rationals, number fields, finite fields, …

The main constructor for the quaternion algebra over F, such that \(i^2 = a\) and \(j^2 = b\) is QuaternionAlgebraStructure::new(F, a, b).

use algebraeon::nzq::Rational;

use algebraeon::rings::quaternion_algebra::QuaternionAlgebraStructure;

use algebraeon::rings::structure::*;

use algebraeon::sets::structure::{EqSignature, MetaType};

let h = QuaternionAlgebraStructure::new(

Rational::structure(),

-Rational::ONE,

-Rational::TWO,

);

let i = h.i();

let j = h.j();

let k = h.mul(&i, &j);

// ij = k and ji = -k

assert!(h.equal(&k, &h.k()));

assert!(h.equal(&h.mul(&j, &i), &h.neg(&k)));Shapes

It is recommended to run the examples in this section in release mode, as the checks performed in debug mode can cause a significant slowdown.

Plotting

To plot a 2D shape, you must create a 2D canvas object, plot any shapes, and run the canvas. A simple example is shown

use algebraeon::drawing::canvas::Canvas;

use algebraeon::drawing::canvas2d::Canvas2D;

use algebraeon::drawing::canvas2d::MouseWheelZoomCamera;

use algebraeon::geometry::parse::parse_shape;

let shape = parse_shape(

"Polygon((0, 0), (6, 0), (6, 6), (2, 3), (0, 4)) \\ Polygon((1, 1), (2, 1), (2, 2), (1, 3))",

);

let mut canvas = Canvas2D::new(Box::new(MouseWheelZoomCamera::new()));

canvas.plot(shape);

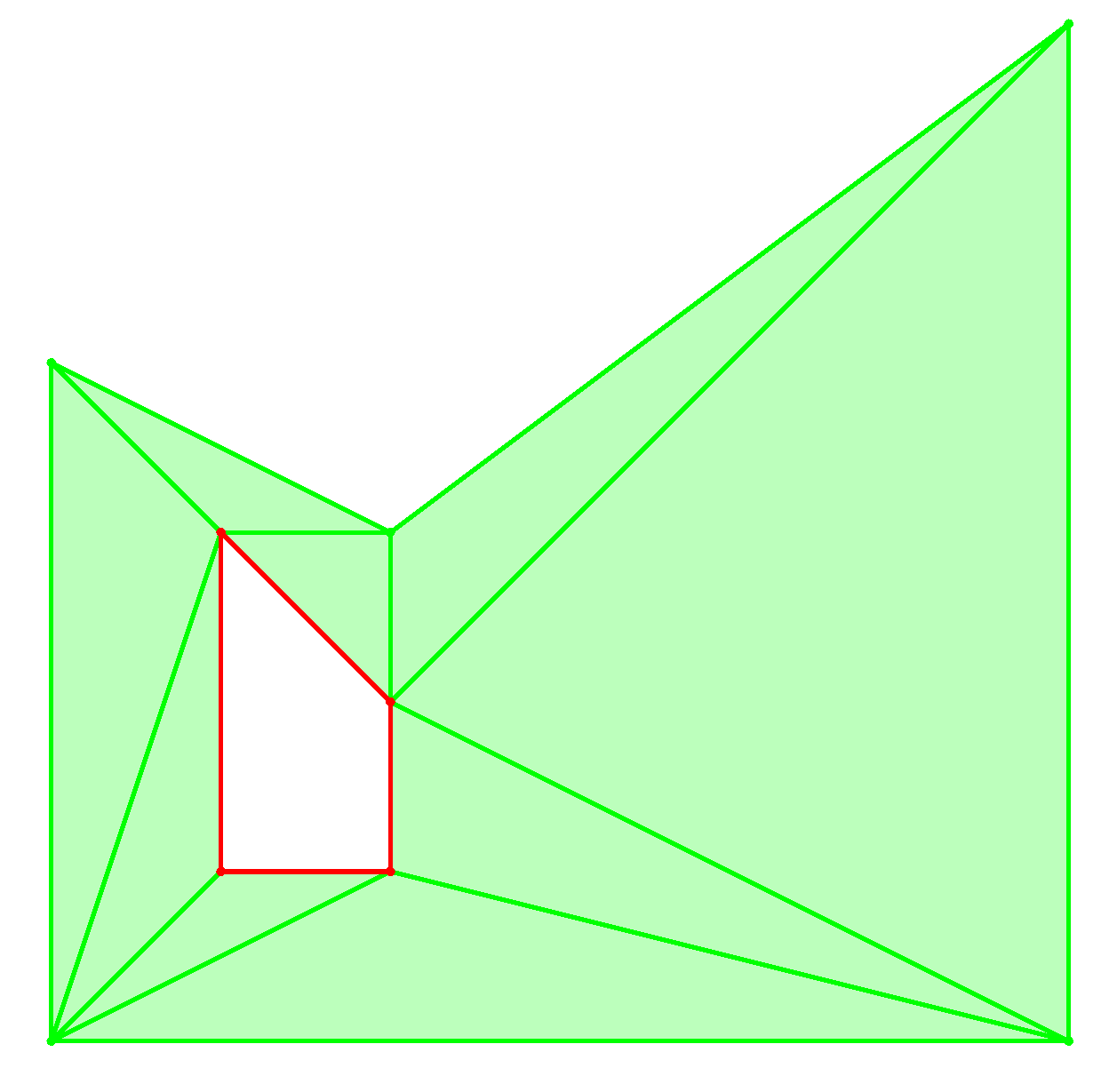

canvas.run();It produces the following plot, in an interactive 2D viewer:

Green areas indicate points that are part of the shape. Red areas indicate boundary points that are not part of the shape.

Loading a Shape From a String

The supported syntax when loading a shape from a string:

Point(<point>): A single point.Lines(<points>): The union of line segments connecting each consecutive pair of points in the list.Polygon(<points>): The closed polygon whose vertices are those given. Only works in 2D.PolygonInterior(<points>): The interior of the polygon whose vertices are those given. Only works in 2D.Loop(<points>): The union of line segments connecting each consecutive pair of points in the list, including the line segment connecting the first and last point.ConvexHull(<points>): The convex hull of the provided points.ConvexHullInterior(<points>): The interior of the convex hull of the provided points. The interior is taken with respect to the affine subspace spanned by the points.ConvexHullBoundary(<points>): The boundary of the convex hull of the provided points. The boundary is taken with respect to the affine subspace spanned by the points.ShapeA | ShapeB: The union of shapes.ShapeA & ShapeB: The intersection of shapes.ShapeA \ ShapeB: The difference of shapes.ShapeA + ShapeB: The Minkowski sum of shapes.